Aliens, a theme quite common in science fiction, have captured imaginations not only in films but also in anime. These mysterious, otherworldly entities from the depths of space have fueled the wildest human fantasies for centuries, ever since the Copernican revolution revealed that Earth isn’t the center of the universe and that the stars above might harbor planets akin to our blue gem in the solar system. If humanity were to encounter a vastly superior species, it would face the ultimate test of our intelligence and the technological achievements built over millennia of civilization. The fear of a destructive power beyond our comprehension has given rise to works that tap into “cosmic horror” or “Lovecraftian horror”—an abstract genre of terror that thrives on the dread of the unknowable, the incomprehensible, stretching far beyond the limits of human thought.

That’s why aliens in movies often appear with terrifying visages. Yet, if the universe we inhabit lacks any intelligent civilizations or species, that reality wouldn’t be any less unsettling. As the renowned sci-fi writer Arthur C. Clarke once said: “Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.” In astronomy, there’s a much-debated concept known as the Fermi Paradox, sparked by Enrico Fermi’s question in 1950: “Where is everybody?” The Fermi Paradox reflects the frustration of scientists searching for extraterrestrial life—decades of effort have yielded no clear signals from civilizations beyond Earth, only silence from the vast expanse. Few realize, though, that the Fermi Paradox can be interpreted in two distinct ways: indirectly and directly.

The Indirect Fermi Paradox

First, the indirect version: “Why, despite our extensive efforts to find concrete evidence of intelligent life beyond our solar system, have we come up empty-handed?” The answer, I think, is fairly straightforward. Space is unimaginably vast, and humanity has only explored a tiny fraction—like a bucket of water in an endless ocean. It could also be due to limitations in our equipment and technology, which may not yet be advanced or sensitive enough to detect their signals. Or perhaps our search methods are fundamentally flawed. In this sense, the indirect Fermi Paradox isn’t all that perplexing—it’s simply a reflection of the current constraints of science when faced with the staggering distances between stars.

The Direct Fermi Paradox

Now, let’s turn to the more chilling version—the direct Fermi Paradox: “If there are civilizations far more advanced than ours, why haven’t they arrived here and turned Earth into a colony?” A galactic empire dominating the Milky Way might sound like pure sci-fi fantasy, but physicist and mathematician John von Neumann proposed a hypothesis that makes it plausible. Imagine if we could create autonomous spacecraft—unmanned, AI-controlled ships capable of self-replication by harvesting raw materials and 3D-printing new robots, while also adapting to the conditions of other planets, much like nature spawns and evolves life. Theoretically, such machines could conquer every planet in the galaxy at current rocket speeds within about 500 million years. That seems like an eternity, but compared to the billions of years of cosmic history, it’s negligible. And if a galactic civilization mastered near-lightspeed travel—tens of thousands of times faster than our capabilities—or even harnessed wormholes or warp drives, colonizing the Milky Way and subjugating every planet would become trivially easy. With von Neumann’s idea in mind, the fact that we’re not living in a Hollywood blockbuster overrun by destructive alien machines becomes oddly perplexing. After all, human history is riddled with invasions by mighty empires, driven by the greed of leaders eager to flex their power and dominate everything in sight.

This is why the direct Fermi Paradox is far more thought-provoking. Many answers have been proposed, but the one that resonates with me most is simple: perhaps we’re not worth it. With only about 200 nations on Earth, conquerors and empires find meaning in seizing another piece of land. But the Milky Way boasts 100 billion stars, most surrounded by planets. Claiming a single planet like Earth would be like strolling onto a sprawling beach and pocketing one grain of sand—a pointless, trivial act.

The mineral resources on Earth’s surface are abundant throughout the universe. The most precious treasures our blue planet holds are water and its rich, diverse life. Yet, we still don’t know if life is truly rare. Even within our solar system, moons of Jupiter and Saturn might harbor marine ecosystems beneath thick icy crusts. Perhaps the direct Fermi Paradox underscores humanity’s smallness and insignificance as we gaze upward at the heavens, at an endless sky.

Hiroya Oku’s Unique Perspective

Among the anime and manga I’ve experienced, one creator stands out for his distinctive take on humanity’s triviality: Hiroya Oku, with his renowned works Gantz and Inuyashiki. So, in this article, let’s dive into these two fascinating yet polarizing stories.

Gantz

Gantz kicks off with its protagonist, Kei Kurono, unexpectedly reuniting with his childhood friend Masaru Katou at a subway station. Out of nowhere, they spot a drunken man who’s fallen onto the tracks. Katou, ever the altruist, leaps down to save him but needs Kei’s help. Kei answers the call, but it’s too late. A train barrels in, snuffing out both their lives. Just when it seems all is lost, they awaken in a strange room with a massive black sphere at its center. Little do they know, they’ve been ensnared in a brutal game of life and death called Gantz.

Gantz is a profoundly unfair game—its players are thrust in blind, with no prior knowledge. They’re equipped with cutting-edge weapons and durable armor to protect themselves, but it’s still not enough. The “monsters” they must eliminate are extraterrestrial beings with overwhelming power, far surpassing humanity and wielding the most outlandish abilities imaginable. Players are left to adapt on the fly, piecing together information bit by bit.

The game’s injustice shines through its sheer ruthlessness, dragging in participants from all walks of life—the worst dregs of society, innocent children, ordinary elderly folks. Their morals or beliefs don’t matter. In Gantz, there are only two kinds of people: the bold and the mundane; the hunters and the unlucky prey.

One thing I love about Gantz is how it portrays fear. You’ll often see characters frozen in terror before overwhelmingly powerful entities, unable to act or fleeing in panic. These moments can frustrate readers, leaving you shouting, “Why don’t they just shoot already?!” But many miss that Gantz isn’t told from humanity’s perspective—it’s from the viewpoint of the superior beings who crafted this game. To them, humans are no different from ants. We still carry primal animal instincts to protect ourselves, like running from fear instead of charging into danger for others.

That’s why Gantz is the ultimate game for the weak. Humanity is no longer Earth’s dominant species but sits at the bottom of the food chain, where our ugliest, most vicious traits are laid bare.

One lesson I’ve taken from Gantz is that Hiroya Oku is a fearless creator—he holds nothing back. With its relentless violence, gore, and provocative elements, some might call Gantz excessively edgy. It is edgy, no doubt, but what I adore is its sheer madness.

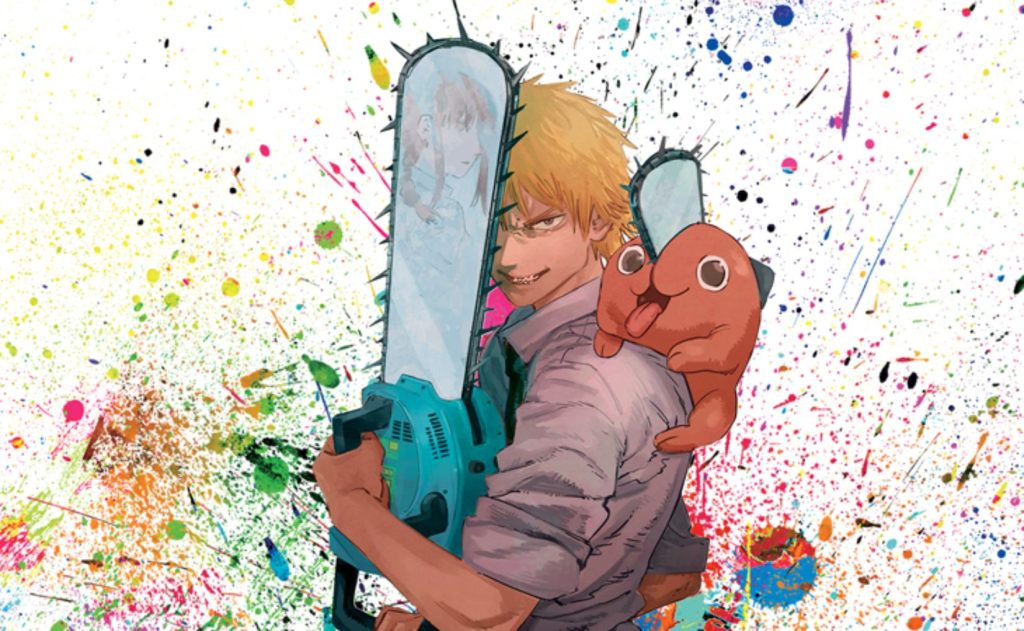

After years of reading and watching countless manga and anime, I can confidently say Gantz is the wildest of them all. Sure, other series have insane arcs—like the international assassin arc in Chainsaw Man—where nothing is predictable. But no work sustains that level of insanity across 380 chapters without ever letting up, like a rollercoaster with no brakes. For me, Gantz is addictive. Each of the two or three times I’ve read it, once I start, I’m hooked for at least a hundred chapters straight—it’s nearly impossible to put down.

What makes Gantz so “mad”? I think it’s how Oku crafts alien monsters with intelligence and emotions akin to humans. Throughout the series, these extraterrestrial beings grow increasingly diverse and powerful, drawing inspiration from celebrities, religions, folklore like yokai, and sci-fi classics like Avatar or Parasyte. Their forms are unpredictable and ever-changing—take the arc where characters face a robot-like figure singing an eerie tune, only to reveal it’s controlled by bird-like aliens. Who’d expect birds piloting mechs and a boss that throws punches? Or the Osaka arc, where the Nurarihyon-inspired boss splits instantly into countless forms, including a grotesque creature made of thousands of female torsos. What am I even reading? Hiroya Oku’s imagination is truly extraordinary.

That said, sometimes he overcooks it—like introducing cool vampires only to drop them by the final arc without a trace.

Amid the relentless chaos of battles with no clear good or evil, what lingers for readers? Despite the story’s perspective—divine entities viewing humans as we view insects—and its unflinching depiction of our weaknesses and society’s dark underbelly, I believe Gantz brims with humanity, especially through Kei Kurono.

At the start, Kei embodies a typical modern teen: selfish, self-absorbed, and crude. But he matures over time, and readers can feel the growing sense of compassion within him. Through this life-or-death game, he gains friends, comrades, and loved ones he feels duty-bound to cherish and protect. From the burdens of heroism, he learns to live for others and realizes life’s meaning lies not in the individual but in the bonds connecting us.

We see similar growth in other characters. Daizaemon Kaze, a martial artist obsessed with being the strongest, discovers through Gantz that strength isn’t for show—it’s for protecting the weak. Hiroto Sakurai, who once honed psychic powers for revenge against bullies, later uses them to help others.

To these godlike beings with ultimate power, humanity’s struggles are meaningless. Memories are mere data points, and human bodies can be conjured from nothing with ease. Yet, despite the universe’s nihilistic void and the endless night enveloping Earth, moments like Kei’s team sacrificing points to revive his loved ones—or even the most callous characters standing with humanity—shine all the brighter.

So why does Gantz exist? In the “Room of Truth” chapter, high-tier aliens reveal they don’t care about humanity. They equip us with futuristic tech to protect Earth and its creatures from migrating aliens. I find this logic shaky—if they’re indifferent to us, why bother with Earth’s fate at all?

Inuyashiki

This is where Hiroya Oku’s later work, Inuyashiki, steps in, delving closer to the direct Fermi Paradox I mentioned earlier. It begins with two drunken aliens crashing their “vehicle” into an old man and a teenager, killing them instantly. Fearing galactic police, they resurrect the victims as robots and flee the scene. The catch? The tech they leave behind is so powerful it could destroy the world. Apparently, they couldn’t care less—just focused on escaping the cops.

Inuyashiki starts oddly and humorously, yet it fits the concept of beings wielding godlike power.

Compared to Gantz, Inuyashiki is more concise, avoiding stray plot threads like the vampire subplot. But it lacks Gantz’s wild edge and feels more predictable.

It follows Oku’s familiar character-growth formula, highlighting duality as a reflection of humanity’s good and evil. This time, it centers on two protagonists: the heroic old man Inuyashiki and the villainous teen Shishigami.

Unlike Kei Kurono, who starts as merely selfish, Shishigami takes it to an extreme. After gaining superhuman power, he turns to destruction and death. Inuyashiki, meanwhile, seeks to save others.

Their opposing paths are clear from the outset, setting up an inevitable clash. But the twist? The villain isn’t purely cold-blooded. Bearing the pain and loss from his actions, Shishigami feels human emotions. Inuyashiki, through his good deeds, finds happiness as a hero—also deeply human.

They don’t just represent good and evil but the emotions and connections vital to life: joy and sorrow, hope and despair.

In a grim world of ruthless thugs and crime, Inuyashiki still offers hope through an elderly man nearing death, showcasing the value of life and compassion. Through Shishigami, accepting consequences and pain reveals what it means to be human.

Final Thoughts

Reflecting on Hiroya Oku’s standout works, I recall a favorite scene from the manga Phoenix: Gaou, a man who committed countless sins and paid dearly—losing family and both arms—exclaims after it all: “How beautiful! The world is breathtaking!” This reinforces my belief that “dark” stories aren’t meant to drown us in despair. The darkness only amplifies the precious light within us all.