When you read the title of this article, you might think, “Wait a minute, SUBA! Didn’t I hear that Miyazaki-san is already working on a new film and hasn’t fully retired yet?” I’m well aware of that. However, Miyazaki-san is now in his eighties, and considering he spent over seven long years on this latest project, I believe he approached it with the mindset that it could be his final masterpiece. With that in mind, it’s hard to imagine him passing up the chance to leave behind messages and a farewell for his audience and fans.

With this thought buzzing in my head, I was eagerly awaiting the day this film would hit theaters in Vietnam so I could see it for myself. Why was I so excited for this particular Miyazaki work? Because one of my all-time favorite anime, Shouwa Genroku Rakugo Shinjuu, features a protagonist, Yakumo Yuurakutei, who embodies the archetype of an artist wholly devoted to their craft. These artists sometimes sacrifice personal relationships just to freely explore the horizons of their art and reach the pinnacle of their creativity. Yet, in the end, all they’re left with is the decline of the very art form they spent their lives perfecting, unable to find a successor. What must the inner turmoil of such talented artists feel like in the twilight of their careers? I think the clearest answer lies in the life story of Hayao Miyazaki himself.

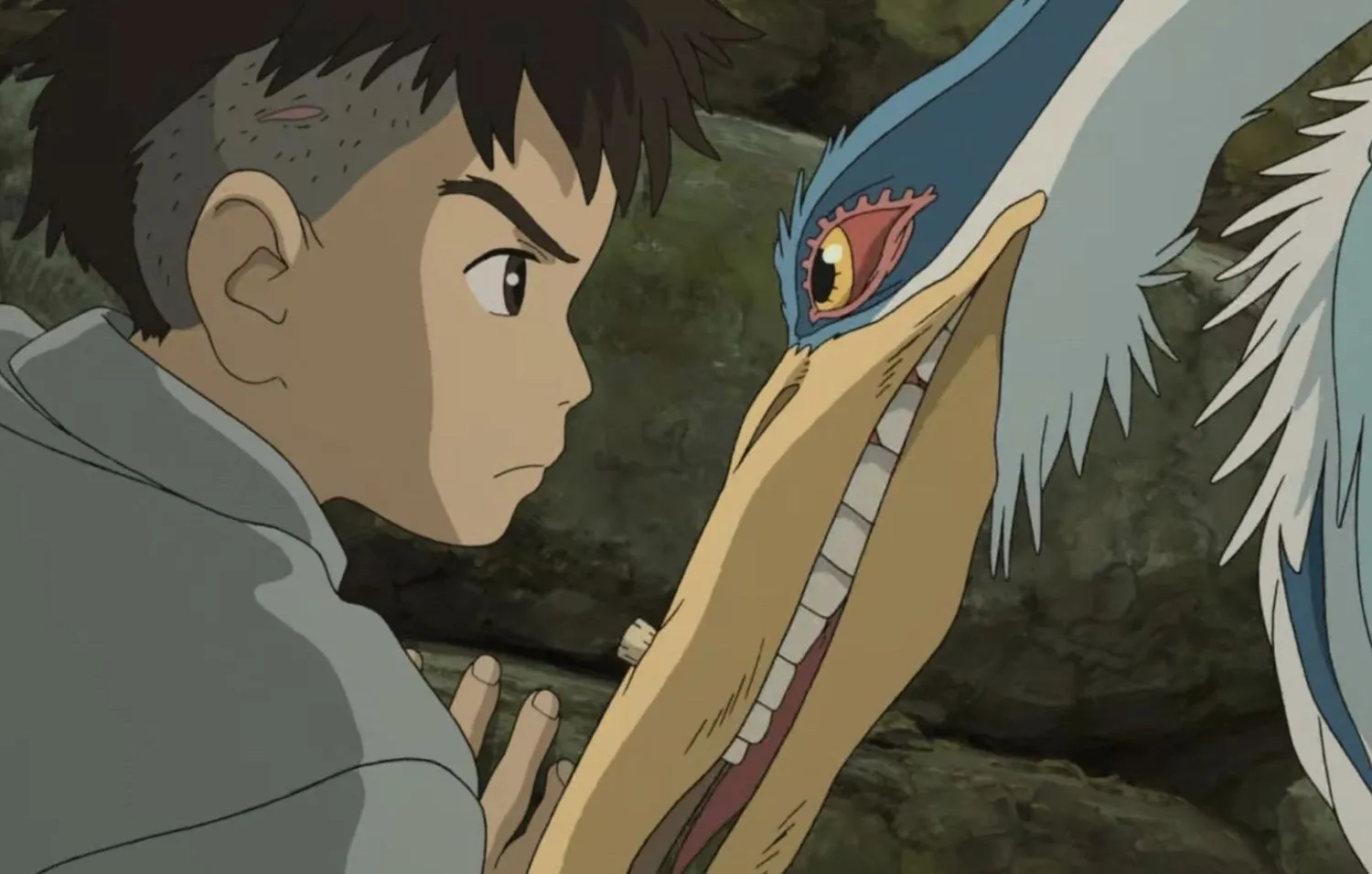

So, in this article, let’s dig deeper into the man, a creator brimming with contradictions, and explore the messages he’s woven into The Boy and the Heron (or, more accurately, How Do You Live?).

Of course, analyzing the film’s meaning inevitably involves spoiling much of its content. So, if you haven’t seen it yet, I’d recommend watching it first before reading on. Alright, let’s start with a brief introduction to this anime.

About The Boy and the Heron

The Boy and the Heron, originally titled How Do You Live? in Japan, is adapted from a 1937 novel by Genzaburo Yoshino. Though it’s labeled an adaptation, a quick peek at Wikipedia reveals that the book’s story and characters differ entirely from the film. To me, the 1937 novel seems more like a spark of inspiration than a direct source. It’s fair to say that no one but Miyazaki-san himself shaped the narrative and characters of The Boy and the Heron, making it a deeply personal work. Online, you’ll find plenty of viewers calling it confusing. Honestly, it’s not that convoluted if you’ve brushed up on Miyazaki-san’s biography beforehand. The protagonist, Mahito, shares so many parallels with Miyazaki’s own childhood that it’s hard to chalk them up to mere coincidence.

A Childhood Echoed in Flames

The film opens with a striking scene of a massive fire. The animators at Studio Ghibli truly outdid themselves here, vividly and realistically capturing the terrifying power of flames that seem to devour everything around young Mahito. For Miyazaki-san, while he didn’t lose his mother to a fire like Mahito does, the haunting childhood memories of desperate screams from victims of World War II bombings left an indelible mark on him. One could say the unforgettable devastation of wartime flames, witnessed at just three years old, ingrained in him a deep-seated love for peace—a theme that echoes through many of his later works.

Like in the film, Miyazaki-san’s family fled the war, moving from Tokyo to the town of Utsunomiya. There, a new home with a stunning garden, a clear lake, and poetic scenery likely sparked his lifelong connection to nature. This bond would become a cornerstone of the artistic style he’d develop in years to come. Another striking similarity is that Mahito’s father runs a factory producing airplane parts, mirroring Miyazaki’s own father, Katsuji Miyazaki.

Miyazaki-san’s childhood was anything but tranquil. At four, he suffered a severe digestive illness that doctors believed would keep him from surviving past twenty. In school, he struggled to fit in with peers, and frequent moves made his teenage years before university, by his own account, a string of mostly unhappy memories. “All I faced was humiliation… so I worked hard to forget it all, and I nearly succeeded,” he once said. Through the film’s early scenes, you can sense this in Mahito’s aloofness and detachment from those around him. The moment where he smashes his own head with a rock to avoid school further reflects Miyazaki-san’s disdain for the memories he longed to bury.

As if escaping a stifling school life, Miyazaki-san discovered a passion for drawing manga, inspired by pioneering artists like Osamu Tezuka. He recalls having a knack for sketching non-human objects with intricate mechanical details—planes, tanks, ships—impressing his classmates. Even into high school, he remained captivated by manga, honing his skills by emulating the styles of prominent mangaka of the era. “I was the only one among my friends truly passionate about manga. If I’d told them I was trying to draw comics, they’d have thought I was an idiot… To me, anyone who didn’t see manga’s potential was the real fool,” he once reflected.

A Life of Contrasts

Looking at Miyazaki-san’s early years, it’s clear his artistic path was one of stark contrast to a reality he saw as “mostly trash.” The fantastical worlds he dreamed up were a curated blend of what he cherished: beautiful nature, admired figures, warm family ties—a reflection of reality filtered through an idealized lens. In The Boy and the Heron, these worlds converge within a “tower” that he and the people at Studio Ghibli spent a lifetime building. Why a tower? I suspect it’s a nod to Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro, Miyazaki’s first theatrical film as a director, which cemented his reputation in Japan.

Characters refer to this tower as an “underworld” or “realm of souls,” concepts familiar from works like Spirited Away or Princess Mononoke. Miyazaki-san deeply believes in Japan’s Shinto faith, a religion that holds that all things—living or not—harbor spirits, giving rise to eight million “kami” (gods) in its tradition. There’s a documentary clip of Miyazaki-san starting his workday: he enters Studio Ghibli, opens the door, and bows respectfully to greet everyone—except no one’s there, as he’s the first to arrive. This glimpse suggests that the Shinto elements in his films aren’t mere inspiration but a reflection of his genuine faith. In this film, Mahito’s journey into the underworld to save his mother echoes the Shinto myth of Izanagi descending to the realm of the dead to revive his wife—one of the tradition’s most famous tales.

Inside the tower, Mahito’s mother appears as a lively, adorable girl, while the elderly maid Kiriko reverts to her youthful, robust self. To me, these details underscore Miyazaki-san’s view of art as a mirror of reality, polished by idealism. He’s even drawn on his own mother’s image in various works to portray the virtues of a good woman, reinforcing this idea.

The Birds of the Tower

The tower’s residents—three bird species: herons, pelicans, and parrots—are perhaps the film’s most abstract and puzzling symbols. Why birds and not some other animal? I think it ties back to Miyazaki-san’s childhood fascination with airplanes, which likely extended to birds. Their effortless flight must have stirred envy in anyone yearning to explore the world freely. Given their subjective nature and close ties to the creator, these images invite viewers to let their imaginations soar and find their own meanings.

I don’t feel compelled to dissect every detail exhaustively here. Still, a few moments stood out to me—like the pelicans, driven by hunger in a fishless underworld, resorting to gobbling up the cute “Warawara” spirits, only to face punishment from Himi. This scene reminded me of underpaid, struggling animators forced to churn out moe-style characters to make anime more marketable. I wouldn’t be surprised if that was Miyazaki-san’s intent, especially since older directors like Masao Maruyama have voiced similar gripes about the industry—a topic I’ve explored in a past article.

Regardless of interpretation, the birds collectively highlight a theme: humanity’s corruption. Pelicans, symbols of noble sacrifice in scripture, now turn greedy and desperate as oceans empty of fish. Parrots, familial fruit-eaters, mimic humans to become a flesh-hungry army. These images reveal Miyazaki-san’s inner conflict over the beautiful world he strives to depict, tethered as it is to a flawed reality he can’t fully escape.

“Today, all human dreams, somehow, are cursed. Beautiful dreams, yet cursed,” he once said.

Miyazaki-san’s life has been a relentless clash between the noble ideals he yearns for and the harsh realities that shatter them. He adores airplanes—marvelous machines fulfilling humanity’s ancient dream of flight—yet watched in horror as his beloved creations became tools of war, sowing terror and death. He crafted anime to inspire people to explore the world and connect with nature, only to see it become the main entertainment for shut-ins glued to their rooms. He built stories brimming with love and family warmth to ease his own cold, troubled heart.

A Late Apology

After watching The Boy and the Heron, I felt it was not only a heartfelt tribute to his mother but perhaps a belated apology as well.

Miyazaki-san’s wife, also an animator, gave up her own passion to become a homemaker, supporting him fully as both mother and father to their family so he could focus on his work. “I owe that kid an apology,” and “My wife probably never forgave me,” he’s said, showing his acute awareness that the sacrifices made for his career were far from trivial.

Similarly, after his father Katsuji’s death, Miyazaki-san lamented never having a serious conversation with him. This regret surfaces in the film when Mahito’s stepmother, Natsuko, lashes out at him—possibly mirroring Miyazaki-san’s self-reproach. His mother, Yoshiko, battled spinal tuberculosis for years, often in frail health, so he may have felt his time with his parents was incomplete, influencing his character choices here.

A Legacy Left to Fade

The film’s ending encapsulates Miyazaki-san’s stance on artistic succession and his acceptance of life’s natural cycle: what is born must eventually perish.

In 2006, his eldest son, Gorou, an architect who’d just finished the Ghibli Museum, was tapped by some at the studio to direct Tales from Earthsea. The intent was clear: to groom him as a potential heir to Miyazaki-san’s legacy. Yet, at the premiere, a famous clip shows Miyazaki-san bluntly criticizing his son. True, he wasn’t the most responsible father to judge, but I understand his harshness stemmed from wanting the best for Gorou. He didn’t need his son to shoulder the crushing burden of inheriting his career. Imagine the pressure—not just to become an anime director (already a tall order) or a “good” one, but to match or surpass a titan like Miyazaki-san and carry forward his monumental legacy. Gorou’s less-acclaimed works like Tales from Earthsea and Earwig and the Witch show that challenge was simply insurmountable.

This dynamic plays out in the film. When the “Parrot King” insists Himi succeed as tower master due to her bloodline, the current master disagrees, declaring only Mahito fits the role. When they first meet, the master drops a red rose, saying, “You are the one,” signaling Miyazaki-san’s belief that the art he spent a lifetime forging is uniquely his. Even if someone replicated his style down to the last detail, it’d be a hollow imitation. Forcing anyone to inherit his legacy would be futile and fruitless. Let the tower of his dreams and imagination crumble naturally.

Miyazaki-san once burned all his early drawings mimicking前辈 like Osamu Tezuka, a testament to his dedication to forging his own artistic identity. He’d never cheapen a lifetime of effort by casually passing that identity on. The film’s conclusion makes it clear he’s at peace with taking his art with him forever.

“Are you worried about the studio’s future?” he was asked. “The future is clear—it’ll collapse. I can see it coming,” he replied. “No need to worry anymore; it’s inevitable. Ghibli’s just a random name I took from an airplane.”

Facing the tower master’s offer, Mahito chooses to decline, longing to return to his family. After years of expressing a bleak view of life, Miyazaki-san admits here that it’s still worth living for the loved ones by our side. To him, Ghibli is just a name; its true value lies in the mentors, friends, and juniors who shared his vision and poured their hearts into the craft they loved.

After escaping the tower, the heron asks if Mahito brought a keepsake. He reveals a stone fragment gifted by the master. “You might forget us someday, but hold onto it,” the heron says. To me, this final exchange is Miyazaki-san’s message to Ghibli fans and future generations: even if Studio Ghibli fades or is forgotten, use our works as inspiration to create your own worlds.

A Personal Triumph

The Boy and the Heron is tough to judge due to its intensely personal nature. For Miyazaki-san, it may be his artistic peak—a grand culmination of decades of triumphs and struggles, reflected upon with hindsight. Yet, its complex value might not fully resonate with audiences or become widely beloved. This is evident in how Studio Ghibli marketed it in Japan: a single poster of a eerie heron, no trailers, and a vague, expansive title, How Do You Live?. The only draw was “Hayao Miyazaki”—essentially, Ghibli saying, “If that name doesn’t excite you, this isn’t for you.” Despite zero PR and its niche appeal, it topped box offices in Japan and abroad, proof of how deeply fans still cherish Miyazaki-san’s work.

If his art ever dies, I believe it’ll be reborn in a new form. Looking at this year’s anime like Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End, I still see a hunger to craft wondrous, beautiful fantasy worlds. So, rest easy, Miyazaki-san—you don’t need to worry.